Training Aikido

How is Aikido training conducted

Aikido practice begins the moment you enter the dojo! Trainees ought to endeavor to observe proper etiquette at all times. It is proper to bow when entering and leaving the dojo, and when coming onto and leaving the mat. Approximately 3-5 minutes before the official start of class, trainees should line up and sit quietly in seiza (kneeling). (If you are unable to sit in seiza, you may sit cross-legged instead if you ask you instructor).

The only way to advance in Aikido is through regular and continued training. Attendance is not mandatory, but keep in mind that in order to improve in Aikido, one probably needs to practice at least twice a week. In addition, insofar as Aikido provides a way of cultivating self-discipline, such self-discipline begins with regular attendance.

O Sensei teaching at Iwama dojo

Your training is your own responsibility. No one is going to take you by the hand and lead you to proficiency in Aikido. In particular, it is not the responsibility of the instructor or senior students to see to it that you learn anything. Part of Aikido training is learning to observe effectively. Before asking for help, therefore, you should first try to figure the technique out for yourself by watching others.

Aikido training encompasses more than techniques. Training in Aikido includes observation and modification of both physical and psychological patterns of thought and behavior. In particular, you must pay attention to the way you react to various sorts of circumstances. Thus part of Aikido training is the cultivation of (self-)awareness.

The following point is very important: Aikido training is a cooperative, not competitive, enterprise. Techniques are learned through training with a partner, not an opponent. You must always be careful to practice in such a way that you temper the speed and power of your technique in accordance with the abilities of your partner. Your partner is lending his/her body to you for you to practice on -- it is not unreasonable to expect you to take good care of what has been lent you.

Aikido training may sometimes be very frustrating. Learning to cope with this frustration is also a part of Aikido training. Practitioners need to observe themselves in order to determine the root of their frustration and dissatisfaction with their progress. Sometimes the cause is a tendency to compare oneself too closely with other trainees. Notice, however, that this is itself a form of competition. It is a fine thing to admire the talents of others and to strive to emulate them, but care should be taken not to allow comparisons with others to foster resentment, or excessive self-criticism.

If at any time during Aikido training you become too tired to continue or if an injury prevents you from performing some Aikido movement or technique, it is permissible to bow out of practice temporarily until you feel able to continue. If you must leave the mat, ask the instructor for permission.

How do ranks and promotions work in Aikido, and how come there are no colored belts?

According to the standard set by the International Aikido Federation (IAF) and the United States Aikido Federation (USAF), there are 6 ranks below black belt. These ranks are called "kyu" ranks.

Eligibility for testing depends primarily (though not exclusively) upon accumulation of practice hours. Other relevant factors may include a trainee's attitude with respect to others, regularity of attendance, and, in some organizations, contribution to the maintenance of the dojo or dissemination of Aikido.

The testing requirements are very different from style to style and from organization to organisation. They also change over time.

Traditionally, white belts are worn by all mudansha (kyu-ranked i.e. below black belt) Aikidoka, and black belts by yudansha (dan-ranked). While some dojos adhere to this policy, others have adopted systems involving the use of different-colored belts for mudansha, with each color signifying one or two kyu ranks. There are naturally proponents for each system.

What is a hakama and who wears it?

A hakama is the skirt-like pants that some Aikidoka wear. It is a traditional piece of samurai clothing. The standard gi worn in Aikido as well as in other martial arts such as Judo or Karate was originally underclothes. Wearing it is part of the tradition of (some schools of) Aikido.

In many schools, only the black belts wear hakama, in others everyone does. In some places women can start wearing it earlier than men (generally modesty of women is the explanation - remember, a gi was originally underwear).

For a more detailed description, please see the hakama section.

What if I can't throw my partner?

This is a common question in Aikido. There are several answers. First, ask the instructor. Most likely there is something you are doing incorrectly.

Second, Aikido techniques, as we practice them in the dojo, are idealizations. No Aikido technique works all the time. Rather, Aikido techniques are meant to be sensitive to the specific conditions of an attack. However, since it is often too difficult to cover all the possible condition-dependent variations for a technique, we adopt a general type of attack and learn to respond to it. At more advanced levels of training we may try to see how generalized strategies may be applied to more specific cases.

Third, Aikido techniques often take a while to learn to perform correctly. Ask your partner to offer less resistance until you have learned to perform the technique a little better.

Fourth, many Aikido techniques cannot be performed effectively without the concomitant application of atemi (a strike delivered to the attacker for the purpose of facilitating the subsequent application of the technique). For safety's sake, atemi is often omitted during practice. Again, ask your partner's cooperation.

How often should I practice?

As often or as seldom as you wish. However, a mimimum of two practices per week is advised.

How can I practice by myself?

Naturally, Aikido is best learned with a partner. However, there are a number of ways to pursue solo training in Aikido. First, one can practice solo forms (kata) with a jo or bokken.

Second, one can "shadow" techniques by simply performing the movements of Aikido techniques with an imaginary partner. Even purely mental rehearsal of Aikido techniques can serve as an effective form of solo training.

Why should I train with weapons?

Some dojo hold classes which are devoted almost exclusively to training with Jo (staff), Tanto (knife), and Bokken (sword); the three principal weapons used in Aikido. However, since the goal of Aikido is not primarily to learn how to use weapons, trainees are advised to attend a minimum of two non-weapons classes per week if they plan to attend weapons classes.

Doshu Kisshomaru Ueshiba during a demo in Japan

Second, weapons training is helpful for learning proper Maai, or distancing.

Third, many advanced Aikido techniques involve defenses against weapons. In order to ensure that such techniques can be practiced safely, it is important for students to know how to attack properly with weapons, and to defend against such attacks.

Fourth, there are often important principles of Aikido movement and technique that may be more easily demonstrated by the use of weapons than without.

Fifth, training in weapons kata is a way of facilitating understanding of general principles of Aikido movement.

Sixth, weapons training can add an element of intensity to Aikido practice, especially in practicing defenses against weapons attacks.

Seventh, training with weapons provides Aikidoka with an opportunity to develop a kind of responsiveness and sensitivity to the movements and actions of others within a format that is usually highly structured. In addition, it is often easier to discard competitive mindsets when engaged in weapons training, making it easier to focus on cognitive development.

Finally, weapons training is an excellent way to learn principles governing lines of attack and defense. All Aikido techniques begin with the defender moving off the line of attack and then creating a new line (often a non-straight line) for application of an Aikido technique.

When can (or should) a beginner start weapons training?

A student "can" start on the first day. A student "should" start whenever their sensei tells them to. For some instructors, this is also the first day. For others it may be later.

Training the Mind in Aikido

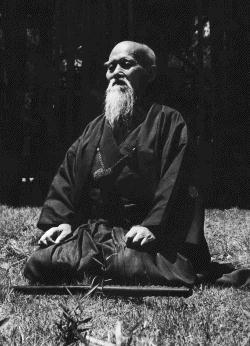

O Sensei meditating

The founder (Morihei Ueshiba) intended Aikido do be far more than a system of techniques for self-defense. His intention was to fuse his martial art to a set of ethical, social, and dispositional ideals. Ueshiba hoped that by training in Aikido, people would perfect themselves spiritually as well as physically. It is not immediately obvious, however, just how practicing Aikido is supposed to result in any spiritual (= psycho-physical) transformation. Furthermore, many other arts have claimed to be vehicles for carrying their practitioners to enlightenment or psycho-physical transformation. We may legitimately wonder, then, whether, or how, Aikido differs from other arts in respect of transformative effect.

It should be clear that any transformative power of Aikido, if such exists at all, must not reside in the performance of physical techniques alone. Rather, if Aikido is to provide a vehicle for self-improvement and psycho-physical transformation along the lines envisioned by the founder, the practitioner of Aikido must adopt certain attitudes toward Aikido training and must strive to cultivate certain sorts of cognitive dispositions.

Classically, those arts which claim to provide a transformative framework for their practitioners are rooted in religious and philosophical traditions such as Buddhism and Taoism (the influence of Shinto on Japanese arts is usually comparatively small). In Japan, Zen Buddhism exercised the strongest influence on the development of transformative arts. Although Morihei Ueshiba was far less influenced by Taoism and Zen than by the "new religion," Omotokyo, it is certainly possible to incorporate aspects of Zen and Taoist philosophy and practice into Aikido. Moreover, Omotokyo is largely rooted in a complex structure of neo- shinto mystical concepts and beliefs. It would be wildly implausible to suppose that adoption of this structure is a necessary condition for psycho-physical transformation through Aikido.

So far as the incorporation of Zen and Taoist practices and philosophies into Aikido is concerned, psycho-physical transformation through the practice of Aikido will be little different from psycho-physical transformation through the practice of arts such as karate, kyudo, and tea ceremony. All these arts have in common the goal of instilling in their practitioners cognitive equanimity, spontaneity of action/response, and receptivity to the character of things just as they are (shinnyo). The primary means for producing these sorts of dispositions in trainees is a two-fold focus on repetition of the fundamental movements and positions of the art, and on preserving mindfulness in practice.

The fact that Aikido training is always cooperative provides another locus for construing personal transformation through Aikido. Cooperative training facilitates the abandonment of a competitive mind-set which reinforces the perception of self-other dichotomies. Cooperative training also instills a regard for the safety and well-being of one's partner. This attitude of concern for others is then to be extended to other situations than the practice of Aikido. In other words, the cooperative framework for Aikido practice is supposed to translate directly into a framework for ethical behavior is one's daily life.